Buddhism's Many Forms and Their Cultural Effects

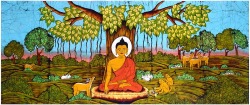

The origin of Buddhism began with meditation under a fig tree and then... a revelation. It began in India, based on Siddhartha Gautama's teachings (c. 566- 486 B.C.). He became known as the Buddha or "Enlightened One". Eventually it spread from India to China to Korea and then Japan.

Japan adapted some foreign customs and ideas to meet their needs in the A.D. 500s. Prince Shotoku supported it, so it spread rapidly. It was practiced with the ancient Shinto religion and had a large impact on Japanese culture. Many forms developed. At first nobility took it up, and eventually, the common people.

Many liked the belief that peace and happiness originated from living wisely and virtously. These are some of the reasons that people joined. Tendai focused on the study of writing. Shingon was about complex rituals. Amida or Pure Land taught a belief of salvation in a pure land after death. Finally, Zen believed that something precious and divine is in each person.

Some types flourished, but others died out. The forms were adopted according to certain preferences and needs of beliefs and practices.

The "beautiful scriptures, golden statues, and Buddhist priests clothed in brightly colored robes... caught the attention and admiration of the Japanese" (Morton, p.17).

They "began to integrate the religious aspects of Buddhism into their society" (Morton, p.17).

Japan adapted some foreign customs and ideas to meet their needs in the A.D. 500s. Prince Shotoku supported it, so it spread rapidly. It was practiced with the ancient Shinto religion and had a large impact on Japanese culture. Many forms developed. At first nobility took it up, and eventually, the common people.

Many liked the belief that peace and happiness originated from living wisely and virtously. These are some of the reasons that people joined. Tendai focused on the study of writing. Shingon was about complex rituals. Amida or Pure Land taught a belief of salvation in a pure land after death. Finally, Zen believed that something precious and divine is in each person.

Some types flourished, but others died out. The forms were adopted according to certain preferences and needs of beliefs and practices.

The "beautiful scriptures, golden statues, and Buddhist priests clothed in brightly colored robes... caught the attention and admiration of the Japanese" (Morton, p.17).

They "began to integrate the religious aspects of Buddhism into their society" (Morton, p.17).

Tendai

Tendai began as a study of the Lotus Sutra, a important Mahayana Buddhist text. In the 3rd century A.D., it was brought to China, and later Zhiyi, a monk, founded a monastery on Mount Tiantai to teach his understanding of the text. It was organized into parts consisting of "various levels of teaching revealed by the Buddha and culminating in the Lotus Sutra, the supreme synthesis of Buddhist doctrine" (http://alumni.ox.compsoc.net/~gemini/simons/historyweb/tendai.html).

Tendai spread, adding information and causing other changes. Nagarjuna's threefold truth was used:

(1) Everything is void and without neccessary reality.

(2) Everything has provisional reality.

(3) Everything is absolutely unreal and provisionally real at the same time.

Tendai spread, adding information and causing other changes. Nagarjuna's threefold truth was used:

(1) Everything is void and without neccessary reality.

(2) Everything has provisional reality.

(3) Everything is absolutely unreal and provisionally real at the same time.

Shingon

Shingon means the "true word". Another monk, Kukai, during Japan's Heian period (794-1185), studied esoteric Buddhism. He made his own interpretation based on Buddha Vairocana.

Belief says that the holy Shingon texts were ruled by Vairocana and hidden until after his death. "The historical Buddha and his teachings were held to be merely one manifestation of Vairocana" (http://alumni.ox.compsoc.net/~gemini/simons/historyweb/shingon.html).

Vairocana was mixed with Dharmakaya (Ultimate Reality), making a embodying figure. Followers believe it was inside everything. "The goal of Shingon was the realization that one's nature was identical with Vairocana, achieved through contemplation and ritual practices" (Shingon Buddhism). It was founded on knowing the oral secret doctrine. Involvement included showing devotion, also called mudras, speaking special dormulae, or mantras, and meditation. Two holy mandalas were located on altars for meditation focus.

In Japan, the year 819, he started a monastery "on Mount Koya, south of Kyoto, which became a great Shingon centre" (Shingon Buddhism). He was artsy and smart, which helped its popularity among all classes, including the "cultivated Heian aristocracy" (Shingon Buddhism). Worship was fun and stunning because:

1) pretty mandalas

2) amazing statues

3) elaborate ceremonies

Also, simple Shingon mantras and mudras were used as fortune and anti-evil charms.

Shingon is now a main Buddhist sect from the Heian period. It was more popular than earlier Buddhist branches and its great rival, Tendai Buddhism. Eventually it mixed with Shinto, the native Japanese religion, supporting Ryobu Shinto's system (or "Dual Aspect Shinto") Vairocana was identical as Shinto's sun goddess Amaterasu. It lost some popularity at "the end of the Heian era as it grew rich and worldly, and evangelistic movements such as Pure Land Buddhism supplanted it in public affection" (Shingon Buddhism). Today it is still an important sect with about 12 million followers.

Belief says that the holy Shingon texts were ruled by Vairocana and hidden until after his death. "The historical Buddha and his teachings were held to be merely one manifestation of Vairocana" (http://alumni.ox.compsoc.net/~gemini/simons/historyweb/shingon.html).

Vairocana was mixed with Dharmakaya (Ultimate Reality), making a embodying figure. Followers believe it was inside everything. "The goal of Shingon was the realization that one's nature was identical with Vairocana, achieved through contemplation and ritual practices" (Shingon Buddhism). It was founded on knowing the oral secret doctrine. Involvement included showing devotion, also called mudras, speaking special dormulae, or mantras, and meditation. Two holy mandalas were located on altars for meditation focus.

In Japan, the year 819, he started a monastery "on Mount Koya, south of Kyoto, which became a great Shingon centre" (Shingon Buddhism). He was artsy and smart, which helped its popularity among all classes, including the "cultivated Heian aristocracy" (Shingon Buddhism). Worship was fun and stunning because:

1) pretty mandalas

2) amazing statues

3) elaborate ceremonies

Also, simple Shingon mantras and mudras were used as fortune and anti-evil charms.

Shingon is now a main Buddhist sect from the Heian period. It was more popular than earlier Buddhist branches and its great rival, Tendai Buddhism. Eventually it mixed with Shinto, the native Japanese religion, supporting Ryobu Shinto's system (or "Dual Aspect Shinto") Vairocana was identical as Shinto's sun goddess Amaterasu. It lost some popularity at "the end of the Heian era as it grew rich and worldly, and evangelistic movements such as Pure Land Buddhism supplanted it in public affection" (Shingon Buddhism). Today it is still an important sect with about 12 million followers.

Amida or Pure Land

Pure Land Buddhism (called Shin Buddhism and Amidism) is founded on their sutras. An Shih Kao and Lokaksema brought them to China. These sutras focus on another Buddha, Amitabha (Amida), known for wisdom and Sukhavati, his Paradise.

A monastery on Mount Lushan built by Hui-yuan in 402 CE, began to spread it in China and Shantao later organized it (613-681). Amida spread to Japan, growing until Honen Shonin (1133-1212) made it independent, so it was known as Jodo Shu. Today, it is the most practiced form in Japan.

The teaching is that nirvana is not practical or possible in the present, but one devotion themselves to Amida, which will let you to go to the Pure Land. It is a Heaven or Paradise, a pleasant place where karma does not exist, to make nirvana an easy goal.

Most chant the devotion mantra, "Namu Amida Butsu," to keep a good state of mind and go to the Pure Land after life. Its simplicity contributed mostly to its popularity in Japan.

A monastery on Mount Lushan built by Hui-yuan in 402 CE, began to spread it in China and Shantao later organized it (613-681). Amida spread to Japan, growing until Honen Shonin (1133-1212) made it independent, so it was known as Jodo Shu. Today, it is the most practiced form in Japan.

The teaching is that nirvana is not practical or possible in the present, but one devotion themselves to Amida, which will let you to go to the Pure Land. It is a Heaven or Paradise, a pleasant place where karma does not exist, to make nirvana an easy goal.

Most chant the devotion mantra, "Namu Amida Butsu," to keep a good state of mind and go to the Pure Land after life. Its simplicity contributed mostly to its popularity in Japan.

Jodo Buddhism

Jodo is the oldest Amida school in Japan. Honen, a Tendai monk, founded it in 1133-1212, after converting to Pure Land at 43. He taught that "anyone can be reborn in Amida's Pure Land simply by reciting the nembutsu and insisted that Pure Land be considered a separate sect of Japanese Buddhism" (http://www.religionfacts.com/buddhism/sects/pure_land.htm).

Shinran, the Jodo Shinshu school founder, and Ippen, the Ji school founder (1239-89), were both followers and monks.

Shinran, the Jodo Shinshu school founder, and Ippen, the Ji school founder (1239-89), were both followers and monks.

Jōdo Shinshū Buddhism

The "True Pure Land School", taught Shin or Shin-shu Buddhism, a Pure Land branch started in Japan by the Shinran (1173-1262) and sorted by Rennyo (1414-99). "It is a lay movement with no monks or monasteries and is based on simple but absolute devotion to Amida. In Shin-shu, the nembutsu is an act of gratitude, not one of supplication or trust" (http://www.religionfacts.com/buddhism/sects/pure_land.htm).

This branch was created by the knowledge of mappō, or Dharma's decline. "Shinran saw the age he was living in as being in a degenerate age where beings cannot hope to be able to extricate themselves from the cycle of birth and death through their own power, or jiriki" (Jōdo Shinshū). Trying to achieve enlightenment and realize Bodhisattva's ideal was made in selfish ignorance. He said it was "inauthentic in nature, for humans of this age and beyond are so deeply rooted in karmic evil as to be incapable not only of attainment but also of the truly altruistic compassion that is requisite in becoming a Bodhisattva" (Jōdo Shinshū).

This Buddhism teaches tariki, or Other Power reliance, the never-ending power if Amida's compassion shown in the Primal Vow to get liberation. Shin Buddhism can is a "practiceless practice," as no specific acts are performed.

During the 17th century, Jōdo Shinshū split into two groups: Otani and Honganji. Both located a main temple in Kyoto and Japan, and are very influential. There are groups of sub-sects. In the U.S., one sub-sect, the Nishi-Hongwanji works as the Buddhist Churches of America.

This branch was created by the knowledge of mappō, or Dharma's decline. "Shinran saw the age he was living in as being in a degenerate age where beings cannot hope to be able to extricate themselves from the cycle of birth and death through their own power, or jiriki" (Jōdo Shinshū). Trying to achieve enlightenment and realize Bodhisattva's ideal was made in selfish ignorance. He said it was "inauthentic in nature, for humans of this age and beyond are so deeply rooted in karmic evil as to be incapable not only of attainment but also of the truly altruistic compassion that is requisite in becoming a Bodhisattva" (Jōdo Shinshū).

This Buddhism teaches tariki, or Other Power reliance, the never-ending power if Amida's compassion shown in the Primal Vow to get liberation. Shin Buddhism can is a "practiceless practice," as no specific acts are performed.

During the 17th century, Jōdo Shinshū split into two groups: Otani and Honganji. Both located a main temple in Kyoto and Japan, and are very influential. There are groups of sub-sects. In the U.S., one sub-sect, the Nishi-Hongwanji works as the Buddhist Churches of America.

Zen

Zen greatly influenced culture. It became common starting in the 1100s. Self-discipline, simplicity, and meditation were emphasized. Zen means "meditation". Followers of Zen believed that silent meditation was more important than ceremonies or scriptures. Just like its emphasis, it was simple. Inner peace was strived for instead of salvation. Samurai joined because of the belief in inner peace and help in battle. The combination of simplicity and boldness was appealing to artists who showed it in their work with black ink and strong, dark lines. Eventually, it spread to other places and became popular in the West.